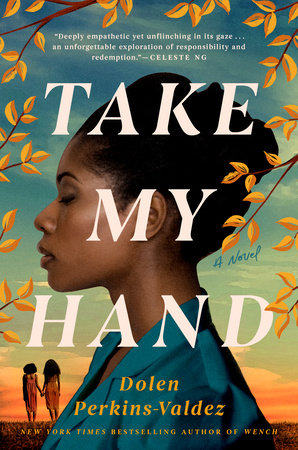

It's 1973 in Montgomery, Alabama, and Civil Townsend has just started her job as a nurse at a Family Planning Clinic. The Clinic serves all women, but mainly those who are poor, Black, and on some type of public assistance. Civil is ready to make a difference, and her first case is two sisters, Erica and India Williams, who are requiring their next round of the birth-control shot Depo-Provera. When Civil arrives at their rundown, one-room cabin, she is shocked by two things: the level of poverty they live in, and the fact that the two girls are only eleven and thirteen. Civil promises herself she won't get involved, but it's nearly impossible not to, when the girls have lost their mother and take so naturally to Civil's presence. As Civil grows closer to the girls, their father, and their grandmother, the unthinkable happens, and Civil is suddenly not so sure whether what she's been doing is really for the greater good or not. Years and years later, Civil begins to tell the story of Erica and India to her own daughter, knowing that those who forget history are doomed to repeat it.

A book like this makes us remember why historical fiction is so important. Not only does it open up a portal to the lives of people years and years ago, but it also makes us aware of things that we otherwise might've been ignorant of. To some degree, I was aware of the history of reproductive violence against women of color, poor women, and the mentally ill -- anyone deemed "unfit" was apparently a prime candidate for birth control, some forms of it much more permanent than others. While we condemn the eugenics that took Germany by storm during Nazi rule, many of us are not as aware of American's own eugenicist past.

From the very beginning of the story, I found myself sympathizing with Civil, rooting for her, and understanding how she struggles with knowing what exactly "the right thing" is. What does that even mean? Especially for those living in poverty, for young black women, for the disadvantaged? It's a question that eats away at her throughout the course of the novel, and her own complicity in the system that belittles those they consider "lesser" is something that she can't forgive herself for. She truly stands out as a heroine, even while she blames herself for many of the horrible things that happen to the two little girls she loves as her own. I liked that, although this is a story that is ultimately hopeful, Perkins-Valdez doesn't hesitate to let us sit with sorrow, with the "what-ifs" that plague both Civil and the Williams family as they try to process the horror done to them.

Although Perkins-Valdez's writing is simplistic, verging on the slightly dry, it somehow works perfectly for the story being told, as well as for Civil's practical voice, and this style works excellently in Perkins-Valdez's capable hands. The plot and pacing are all wonderfully executed, though I would argue that this story is more character-driven (which is, personally speaking, my favorite kind of story). It is India and Erica who motivate the entirety of the narrative, and it is they who drive Civil to becoming the person that she is. There's undoubtedly a bittersweetness to Take My Hand, but with its subject matter, how could it not be? It felt appropriate for the tale being told, and I applaud Perkins-Valdez for her beautiful way of handling a story that is so fraught with pain and anger.

Highly recommended.

NOTE: In Perkins-Valdez's afterword, she goes on to discuss reproductive violence and reproductive justice. Today, Black women are over three times more likely to die in pregnancy (and postpartum) than white women. That is just one of the many huge issues facing Black women's reproductive health -- they are also more likely to experience uterine fibroids, have less access to contraceptives and research shows that Black women receive less quality care than white women.

Resources on Reproductive Justice:

National Black Women's Reproductive Justice Agenda